Article

Design That Listens: Lessons from the V&A’s Design & Disability Exhibition

In late 2025, one of our consultants, Cat, visited the Design & Disability exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The exhibition explored the contributions of disabled people to design and contemporary culture from the 1940s to today, centring disabled voices not as an afterthought, but as innovators, creators, and agents of change.

For us at King & Allen, this visit was part of a wider commitment: to engage with important conversations, to deepen our understanding, and to continually reflect on how we can offer the most thoughtful, inclusive service possible. We don’t believe learning is ever “done”, and this exhibition offered valuable moments of reflection that directly connect to the work we do every day.

Visibility: representation with intent

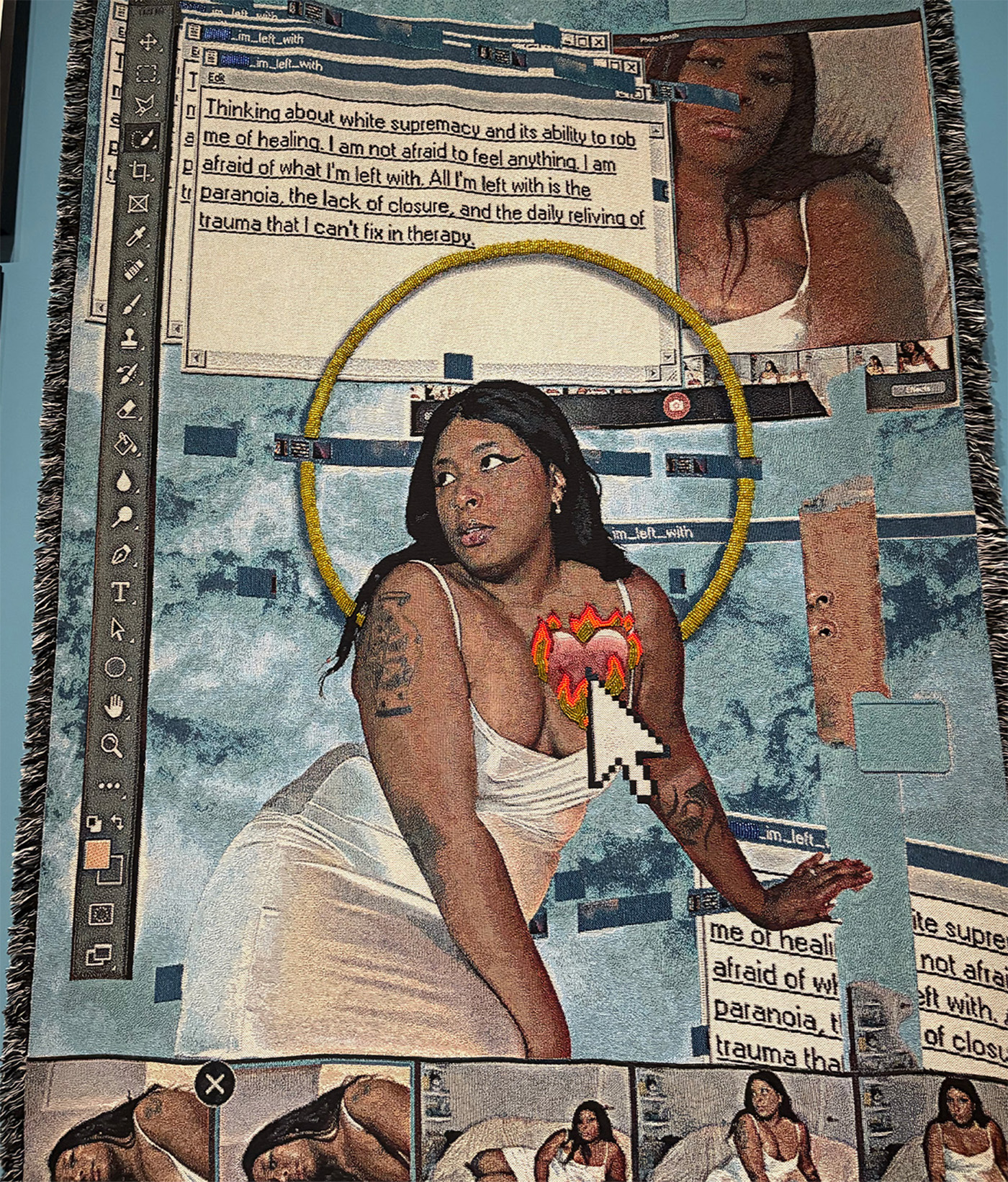

The Visibility section explored how disabled people use design, art, and visual culture to express identity, challenge stereotypes, and be heard. From protest artwork to campaigns created for disabled audiences, the message was clear: representation matters — but only when it’s meaningful.

Cat was struck by how often disabled people are still “othered” in mainstream media, portrayed as objects of pity rather than equals. One powerful display of magazine covers featuring disabled models prompted an important question: why is this kind of representation still treated as exceptional? Despite making up a significant part of the population, disabled people remain largely absent from fashion campaigns.

The takeaway was clear, inclusion can’t be occasional or performative, It has to be consistent, intentional, and rooted in respect.

Tools: design shaped by lived experience

The Tools section showcased objects designed for and by disabled people; practical, expressive, and deeply inventive.

Alongside adaptive clothing made with specific needs in mind were garments that challenged assumptions about how disabled people “should” dress. A standout piece was Maya Scarlette’s carnival costume, The Birth of Venus, which celebrated visibility, confidence, and joy - a reminder that disabled style doesn’t need to be hidden or purely functional.

The exhibition also highlighted everyday adaptations, from modified cutlery to adapted gaming controllers, many of which later evolved into widely used products. It underscored how disability-led design has shaped mainstream technology, including touchscreen interfaces originally developed to improve computer accessibility.

Nike FlyEase trainers offered a compelling example: designed for ease, marketed to everyone. Their success showed how inclusive design, when done well, can support disabled people while benefiting a much wider audience — without singling anyone out.

Living: designing dignity, autonomy, and participation

The final section, Living, explored how disabled people have imagined and shaped the environments they want to live in - through design, protest, and collective action.

Highlights included a vest designed for deaf rave-goers that translates bass vibrations into physical sensation, allowing wearers to feel music as well as hear it. Another was the McGonagle Reader, a device enabling blind people to vote independently via audio guidance, a powerful reminder that access is inseparable from autonomy and dignity.

This section also addressed the more difficult realities of disabled people’s living conditions, past and present. It explored histories of institutionalisation and examined how even today, disabled people can be disproportionately affected by policies that fail to account for care needs, access requirements, or non-standard living arrangements.

Intersectionality: no single experience of disability

One of the most important threads running through the exhibition was intersectionality. Disability does not exist in isolation; experiences are shaped by race, gender, sexuality, and neurodivergence. Diagnosis can take longer for women and people of colour, and neurodivergent people, particularly autistic individuals, are significantly more likely to identify as LGBTQ+.

Recognising these overlapping identities is essential. They influence how people experience their bodies, how they are treated by systems, and how they understand themselves. This complexity reinforces why no two clients, bodies, or needs are ever the same.

What this means for our service at King & Allen

The exhibition reinforced something we already believe: good design starts with listening.

At King & Allen, we work with clients with a wide range of access needs, including wheelchair users, blind and visually impaired clients, and people with mobility or sensory considerations. What this visit affirmed is that there is no “standard” approach. Our clients are the experts in their own bodies and experiences.

Our role is to collaborate, to listen carefully, ask the right questions, and use our tailoring expertise to translate those insights into garments that genuinely support the wearer. That might mean adapting proportions for seated wear, adjusting structure for mobility aids, or refining internal construction for comfort and ease. Often, it also means allowing time and space for conversation, trust, and understanding.

Inclusive design isn’t about ticking boxes. It’s about curiosity, humility, and an ongoing commitment to learning, so that every client feels seen, respected, and supported in finding their fit.