Article

The politics of clothing. Suffragettes, suits and solidarity

On 6 February 1918, more than eight million women won the right to vote, thanks to the introduction of the Representation of the People Act. It would be another decade before all women and men could have their say (another five million men were given the vote under the 1918 act), but it was a significant step forward, not least for the suffragette movement, who had campaigned for more than a decade. The group’s increasingly militant actions are well documented, but what is less well known is the role that clothing played in furthering their cause.

To mark the centenary of this key piece of legislation, King & Allen looks at the role that clothing can play in heightened political times.

What we wear says a lot about us – our personalities, our beliefs, sometimes even our politics. No one knew this better than the suffragette movement.

Named suffragettes by the Daily Mail, the movement was spearheaded by Emmeline Pankhurst who felt a more radical approach was needed to make their point. Over time, Pankhurst and her suffragettes would famously deploy radical tactics, such as violence and hunger strikes, and frequently faced arrest.

Women in suits: an affront to masculinity and domestic life

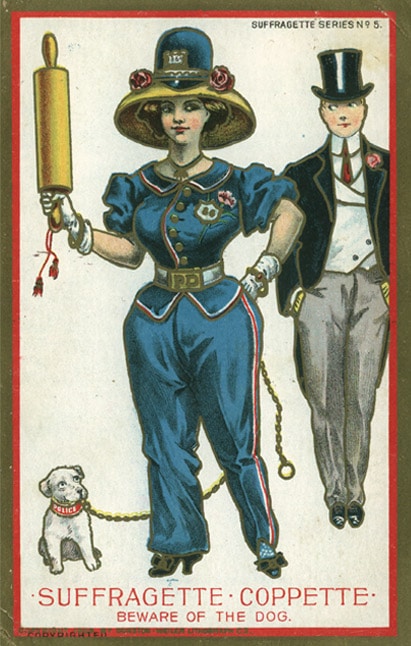

But the way the suffragettes dressed was also a political statement – radical, as it turns out, in its conventionalism. As the call for the women’s right to vote grew, so too did vitriol in certain quarters of the press and cartoons and postcards appeared, mocking suffragettes as ‘mannish’ brow-beaters dressed in suits, cravats and pince-nez, hell bent on demasculinizing their husbands and abandoning their children. In calling on women to use the way they dressed to support the cause, the suffragettes were able to create a united front that spoke volumes. As Cally Blackman wrote in a piece for The Guardian in 2015: “Fashion, feminism and politics has always been heated territory, and the suffragettes knew this.”

As well as urging supporters to be ‘dainty’ and ‘precise’ in their choice of outfits, the movement also adopted common colours – an early example of just how powerful brand recognition can be. As Blackman writes: “it became fashionable to identify with the struggle for the vote, even if only by wearing a small piece of jewellery picked out in semi-precious coloured stones or enamel.”

Grace Evans is Keeper of Costume at Chertsey Museum, where a new Fashion & Freedom exhibition explores the history of female emancipation through clothing. She explains: “Suffragettes knew that clothing was important. They really harnessed the idea of having their own colours – purple for loyalty and dignity, white for purity and green for hope. In an edition of their magazine Votes for Women, it urged women to ‘be guided by the colours in your choice of dress. We have 700 banners in purple, white and green. The effect will be very much lost unless the colours are carried out in the dress of every woman in the ranks. White or cream Tussore should, if possible, be the dominant colour. The purple or green should be introduced where other colour is necessary. If every individual in this union would do her part, the colours would become the reigning fashion and, strange as it may seem, nothing would so help to popularise the WSPU [Women’s Social and Political Union].’ They were really quite detailed and specific and wanted this united uniform to look striking as they marched.”

A century on, this call for unity in clothing has most recently been echoed by the Women’s March movement, whose supporters are encouraged to march wearing pink, knitted ‘pussy hats’.

Despite their traditional approach, many suffragettes were advocates of the ‘aesthetic’ or ‘rational’ dress movement, which campaigned for looser, more comfortable clothing. Items such as the corset had long restricted movement, caused skeletal deformities and exacerbated medical problems. In the US, the movement even had its own ‘suffragette suit’, created in 1910 by the American Ladies Tailors’ Association and featuring a divided skirt that allowed wearers to take long strides.

“A number of suffragettes wore aesthetic dress” says Grace. “Freedom of movement is associated with freedom in general”

This freedom of movement became a practical necessity during the First World War when an increasing number of women joined the workforce. Post-war those changes continued apace and in the 1920s both the flapper girl and women in trousers became familiar sights.

Waistcoats inject personality for men

Changes in male clothing, on the other hand, tend to be more gradual and you have to go back to the 18th Century to a time when men were as restricted by their dress as women, although for both sexes, this was largely a question of status. “Men and women of a certain stature wore highly decorative, impractical clothing,” says Grace. “Fashion was driven by the aristocracy and if you were wealthy you wanted people to know that you didn’t need to work for money you wore expensive clothes that were difficult to move in.”

Like the First World War for women, the onset of Industrial Revolution necessitated a change, and, by the end of the 18th century, a wealthy man was more likely to be dressed in a beautifully cut wool coat or buckskin britches. Throughout the 19th Century, men’s dress continued its sober evolution, although some items, such as the waistcoat, offered the chance to express a little personality. “It was up to you whether you revealed that little bit of yourself,” says Grace. “Charles Dickens was well known for his brightly coloured waistcoats.”

This idea of revelation was used by the suffragettes, too. One of Chertsey Museum’s exhibits is a pair of stockings, hand embroidered in silk with suffragette colours. “The embroidery is on the ankle, which meant you could choose whether to reveal your loyalty or not. Also, the ankles were considered a little risqué in those times, so there’s potentially a rebellious side to it.”

Suits you – unless you’re a Republican presidential candidate

Today, it’s not just political movements that use clothing to make a statement, but it seems our politicians are, too. Of course, female politicians’ fashion choices are regularly scrutinised by the tabloid press, but during the race to become Republicans’ US presidential candidate, many of the runners, such as Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, all swapped traditional suits for identikit zip-up sweaters. This more relaxed look was meant to send a message that these men were just regular guys, standing up for other regular guys. As we know, though, the message didn’t get through and the only man who refused to wear anything other than a suit was one Donald J. Trump.

Throughout history, clothing has been used time and again as a political statement – designer Katherine Hamnett almost single-handedly invented the slogan t-shirt when she wore an anti-missile t-shirt to meet then British prime minister Margaret Thatcher in 1984. And Vivien Westwood’s politics are practically woven into her work. And in these politically challenging times, more and more designers are using the catwalk to express their views. The suffragettes would be proud.

Find out more about the suffrage movement at the Chertsey Museum’s Votes for Women page.